The end of the trolley bag: How the Judiciary made the Criminal Court digital

Source: Technology news from Trinidad and Tobago

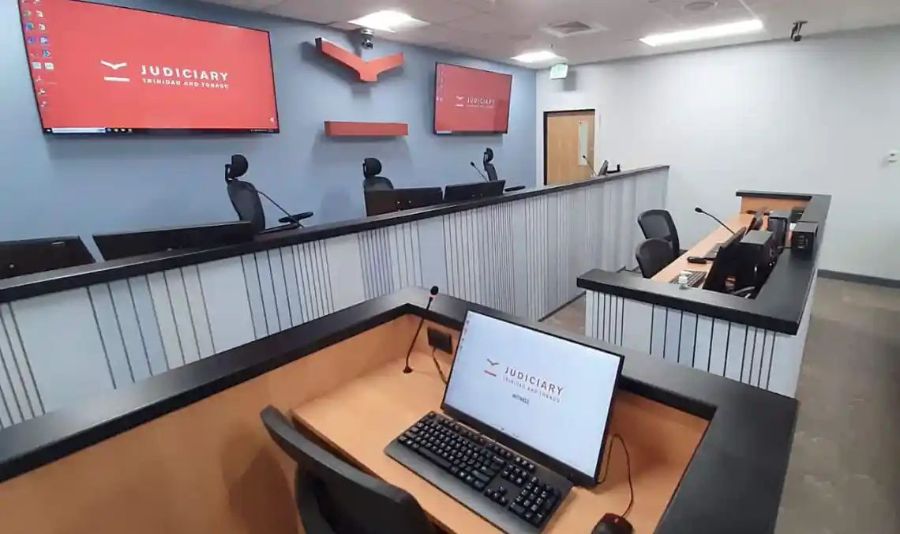

Photo: A courtroom prepared for hearings under AJIPAA. Photo courtesy the Judicicary of Trinidad and Tobago.

By Mark Lyndersay

Sunday 22 January 2024

To begin the movement of indictable cases from preliminary inquiries at District Courts to direct hearings at the High Court, the Judiciary started with a…form.

To be precise, an interlocking system of forms that captures every aspect of case submissions as editable, live data.

Hilwyn Hernandez, Court Web Software Developer, developed the platform, now formally branded SWF (Secure and Simple Web Forms).

“SWF deals with originating documents, but eventually we are looking at moving all documents that are public facing to the platform,” he said.

To make that work for legal purposes. the team had to create verification systems to guarantee authenticity and provenance.

“We are moving strongly to not accepting documents at all, and this is the first step. When we have PDF documents coming in, it’s not data-driven, so our move here is to move to data only as opposed to a document-driven judiciary.”

That commitment extends to verbal presentations in the courtroom, which are captured and transcribed using two voice-to-text transcription services designed for courtroom use, FTR (For the Record) and Audio Scribe’s SpeechCAT technologies.

The Judiciary’s biggest development project was CMS-X, a new case management system. Prior to working with this new code base, the courts were faced with rising fees and sketchy support from a vendor content to deal with captive customers in an extremely vertical market.

CMS-X is derived from a code base supported by the National Center for State Courts of the US and developed by the Supreme Court of Nigeria.

In this unusual case of open source development within a very strictly defined vertical market, what’s emerged is the Consortium, a group of like-minded court administrators keen to escape the lock-in and poor support of vendors with a captive market and willing to push their development innovations back into the source code.

It’s not strictly speaking open-source, but it’s close enough for government work.

The one large commercial code base that the Judiciary will be working with for this major shift to digital court management is Thomson-Reuter’s Case Center, a system for gathering and presenting evidence, taking private notes as the trial progresses and annotating evidence either for public or private viewing.

According to Kern Millien, Records Management Consultant, Case Center is the repository for all the evidence related to a case.

“You may have medical reports. You might have documentary evidence, images, crime scene photos. You might have CCTV footage, voice notes, audio recordings, the full range of different formats.”

“All case participants, attorneys, judge, master or their support staff would be able to upload that evidence. They are all able to upload their evidence, their depositions, their statements, their documents.”

“The defence teams could upload their documents as well. The court would upload any code generated documents, and they all now are able to prepare, working from a singular electronic bundle.”

The technology makes it possible for a lawyer to appear virtually for a case hearing while accessing all their case notes and annotations online and for witnesses to also appear without being physically present in the courtroom.

The core evidence related to the case is continuously present for all parties, ensuring shared awareness of the evidence underlying the case.

This kind of integration of case materials and unified systems for submissions has required the Judiciary to engage in a wide-ranging effort to bring stakeholders together to make the system work.

But even with the best software and systems integration possible, the reality is that it’s people who will have to input and file that information.

The efficient administration of justice will ultimately depend on how comfortable everyone is with the system.

“Based on the feedback from stakeholders about how they will organise their work, how it’s anticipated to work with police [for instance], their case management units can prepare the documents with administrative support staff and then the documents can be reviewed by a senior officer,” said Jaime Philbert, Deputy Court Executive Administrator.

“There are permission access levels built into our system [governing] who can view, who can edit and then move to sign (and submit).”

“This is very much a collaboration,”said Carol Herbert, the Judiciary’s Director-ICT.

“We sit with stakeholders, we run through the system and we get their feedback. As we get that feedback, we respond, whether it’s to add a feature or just try to understand what affects them.”

“We have done that extensively with the police and we met recently with the DPPs office. It’s not us just creating, we are doing this in a collaborative arrangement.”

ICCS implementation

Among the changes introduced by the Judiciary is is the use of codes developed for the International Classification of Crime for Statistical purposes system (ICCS), spearheaded by the Juvenile Court Project of the Judiciary.

The ICCS zones crimes according to policy area (severity of crime), target, seriousness and is intended to both identify and codify crimes more accurately.

The codes represent an opportunity for the Children’s Court to deal with crimes in a more nuanced way, emphasising rehabilitation over punishment.

But, the codification system offers an opportunity to deliver a more detailed picture of criminal activity.

Trinidad and Tobago is the first Caricom island to implement the ICCS.

How AJIPAA is reducing court delays

Even if an accused wished to plead guilty, that was not possible until the following steps had been taken, each of which required its own span of time.

• From the laying of information before a magistrate through to the end of a preliminary enquiry at the district court.

• From the committal order to the dispatch of the committal bundle to the DPP.

• From receipt of the committal bundles to the filing of an indictment by the DPP.

• From the filing of an indictment at the High Court to disposition. With the filing of the indictment, a guilty plea could then be entered.

Under AJIPAA, stages 1,2, and 3 above have been removed and with them, the associated delays.

The fourth stage has been severely truncated into:

a) The filing of a complaint with an immediate initial hearing. This produces a scheduling order which gives a date for the filing of the indictment.

b) Sufficiency hearing (usually within 3 months of the initial hearing). Case management begins here and someone can plead guilty this early. They can plea bargain and prosecution can either be deemed to have sufficient evidence to go ahead or not.

“In most modern jurisdictions,” The Judiciary advised, “fewer than 5-20 percent of cases go to full trial. Others are disposed of by guilty pleas, plea bargaining and other methods.”

“This is also the goal of the Trinidad and Tobago criminal justice system with case management and MSI’s (Maximum Sentence Indications) as some of the tools to get this done.”

Early statistics on the project

Just six weeks into the implementation of AJIPAA, the system is yet to have its first Sufficiency Hearing (expected within two months).

Since the December 12 proclamation of AJIPAA, 287 matters have been filed with the High Court.

Of that number, 144 were transferred to the District Court with 68 matters transferred to the High Court and 211 matters were described as pending.